In the Path of the Flood: A Visit to Johnstown, PA

Skip to Section

Hidden among mountains in Southwestern PA, the city of Johnstown might not seem much like a tourist destination—were it not for the museums, parks and terrain associated with its catastrophic 1889 flood.

Despite that horror—which left 2200 dead and wiped out the city in a mere 10 minutes—what a modern visitor notices first is the area’s quiet, pastoral appeal: rolling hills, winding waterways, meandering two-lanes and rustling, sun-dappled forests.

But then, that bucolic beauty is part of what caused the deluge to begin with.

“A Huge Hill Rolling Over and Over”

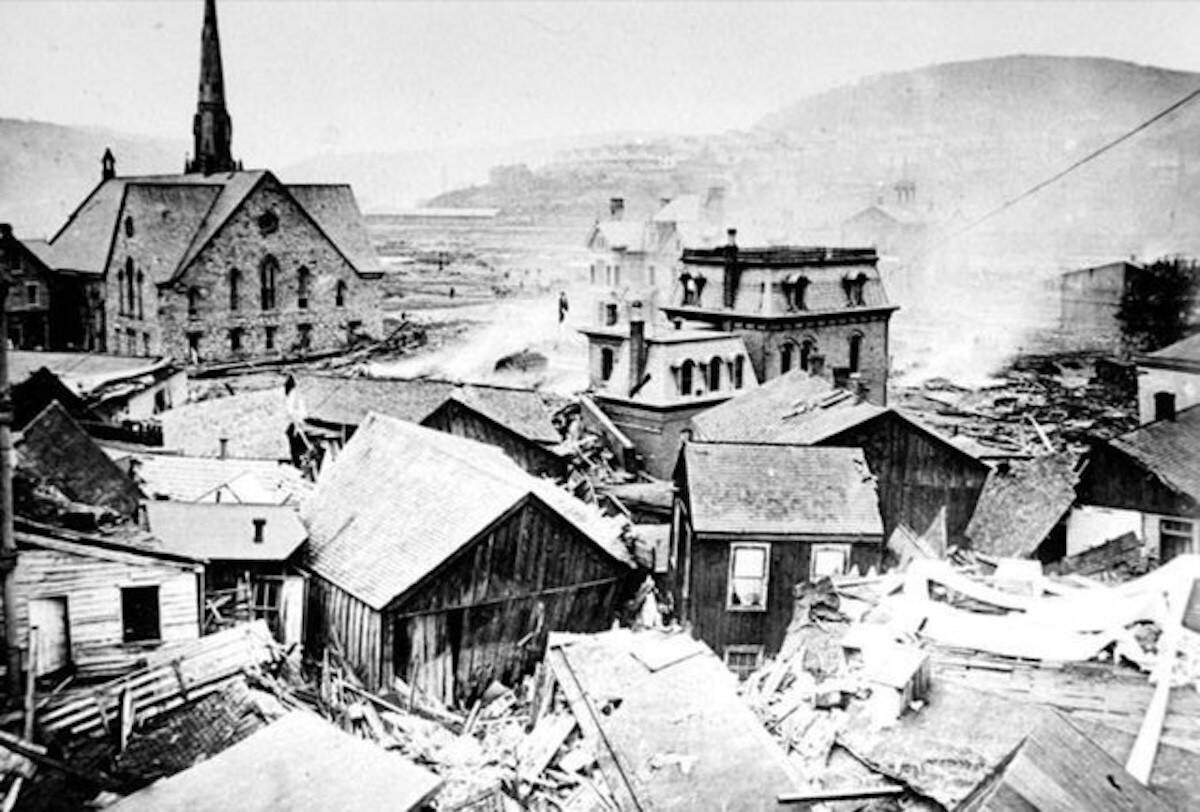

Post-flood houses flung helter-skelter by the 1889 Johnstown Flood. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Initially completed in 1853 as part of a statewide canal system, the South Fork Dam stood 14 miles above Johnstown. In the following decades it fell into disrepair, and the middle had actually collapsed at one point (happily, during a fairly dry season).

In 1879, it was finally sold to a wealthy Pittsburgher who aimed to create a rural vacation getaway for himself and other well-to-do urbanites. The nascent South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club managed to reestablish Lake Conemaugh behind the dam—for boating, fishing and other recreation; but their fixes to the structure were slipshod, with almost no provision for releasing extra lake-water during heavy rains.

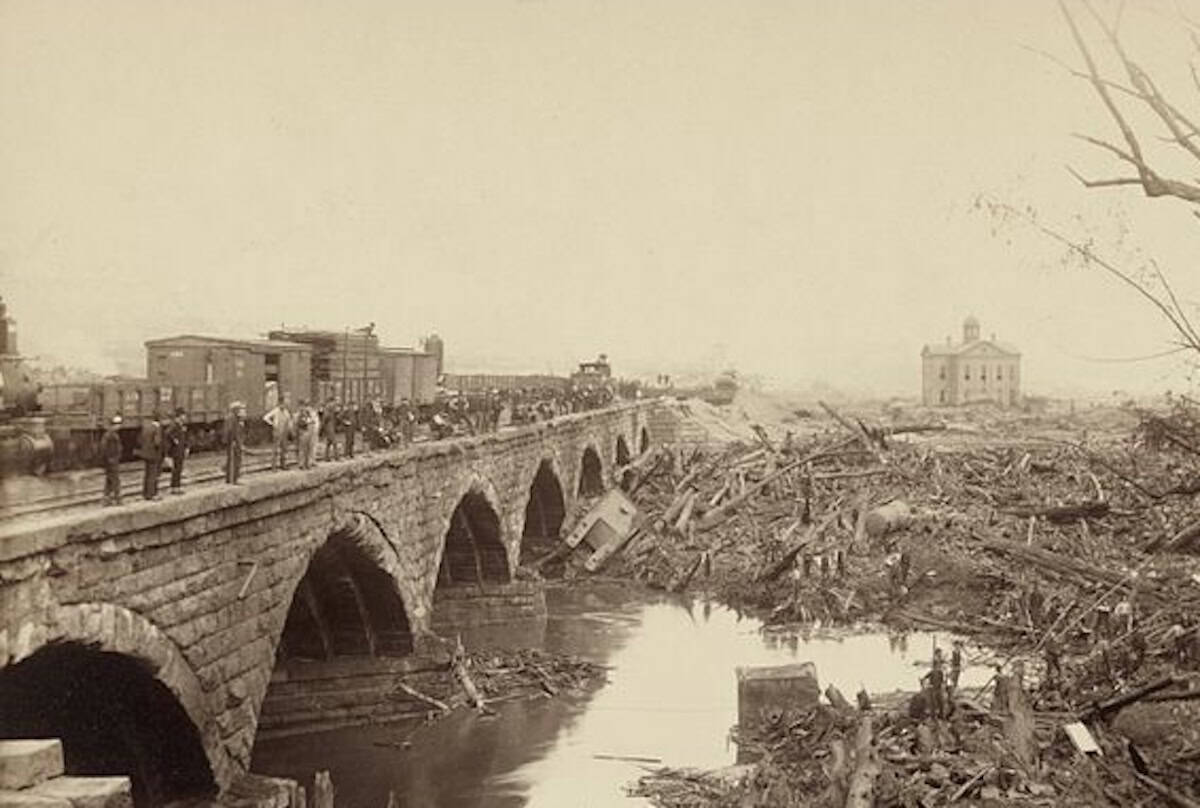

Clean-up begins on flood debris piled against Johnstown’s stone-arch bridge; spreading across 30 acres, this tangled mess had earlier been on fire for days, killing many victims trapped in the rubble. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

On May 31, 1889, after several days of torrential downpour, the weak middle section again gave way. As Lake Conemaugh emptied through the massive gap, 20 million tons of water rushed down the river valley toward Johnstown. Passing through several villages and railyards, it arrived in the city 50 minutes later—looking not so much like a flood as “a huge hill rolling over and over” (in the words of one witness).

By the time it struck, the water was carrying rocks, trees, houses, railcars and 200 tons of cable and barbed wire swept up from the Gautier Steel Company just north of town.

Photos of the resulting devastation look like someone took a garden hose and sprayed it at a model train set.

To make matters worse, much of the debris washed up against a massive stone-arch bridge downtown—where it caught fire and burned for three days; with no one able to navigate this, many died in the fiery wreckage—which eventually covered 30 acres.

The final death toll stood at 2,209; one-third of the bodies were never identified. Property damages totaled $17 million (about half a billion in current buying power).

It remains one of the worst natural disasters of the 19th century.

South Fork Flood Memorial

Current view of the break in the South Fork Dam, which unleashed the Johnstown Flood in 1889. Though hard to see here, there are viewing platforms on what remains of the dam at right and left.

One doesn’t normally start a travel piece with this sort of lengthy historical recap; but Johnstown’s various flood-related sites—some overseen by the National Park Service—attract thousands each year, and the shadow of the deluge hovers everywhere … even after more than 13 decades.

Long fascinated by the disaster, I finally made a summer pilgrimage with my wife this year.

Little Conemaugh River at the Johnstown Flood Memorial; photo taken from the “Walk Through the Ruins,” a trail maintained by the National Park Service. This is where the base of the dam stood; the planks may have been part of the original structure that turned this modest stream into a one-by-two-mile lake—and thereafter, a deadly deluge.

Our first stop was the Johnstown Flood National Memorial near South Fork—well marked with signs off Route 219; this site includes remains of the actual dam. Now entirely covered by weeds, it looks more like two hills than anything else. You can walk out along what’s left on both sides of the infamous breach, with viewing platforms that look down upon the now-placid Little Conemaugh River, plus a trio of Norfolk Southern train tracks.

Also there is the “Walk Through the Ruins,” which takes you right through the gap at ground level. Advertised at 45 minutes, it’s really only 20—but well worthwhile. The trail winds swiftly down to the river, where a set of water-logged planks remain from what must have been part of the 1853 structure—either the long-gone water-control tower, or perhaps the culvert system designed to let water out at the bottom. (Significantly, these iron culverts were sold for scrap and never replaced—one key culprit in the catastrophe.)

“The Path of the Flood”

So-called “debris wall,” a man-made installation at the Johnstown Flood Memorial visitors center.

Just past the dam-gap, the “Ruins” walk turns sharply left, heading back up to the parking lot; if instead you continue straight under the 219 overpass, you’ll be on the “Path of the Flood Trail,” which winds the full 14 miles to Johnstown—following the Conemaugh valley along the same track taken by the deluge.

A friend once ran his first half-marathon in the annual race along that trail; and my wife and I wanted to bike it—before discovering that: 1) it’s often perilously steep; and 2) much of it runs on well-traveled roads—especially when it reaches Johnstown proper. (We did wind up biking some; more on that later.)

On the other side of the creek from the “Ruins” trail stands the impressive NPS visitors center, offering several fascinating features: actual artifacts recovered from the flood; a huge three-dimensional contoured map of the flood-path, complete with tiny lights showing how the water moved; a recorded audio interview with 91-year-old flood survivor Victor Heiser; an often-scary 35-minute movie that really brings the disaster to life; and of course, friendly and knowledgeable park-ranger staff.

Other Floods and Sites

One of seven arches on Johnstown’s stone bridge, where flood debris piled up and caught fire during the catastrophe. This span still carries roughly 50 trains a day, and the city has adorned it with LED lights that come on for three hours every evening.

There is another Johnstown Flood Museum in the city itself; but sadly, that was closed during our visit … due to flooding! (Located at the confluence of the Little Conemaugh and Stonycreek rivers, Johnstown has suffered many other damaging floods, most notably in 1936 and 1977.)

Also closed for “major restoration”: the city’s popular inclined plane. Billed as the world’s steepest, this two-car funicular runs nearly 900 feet up and down Yoder Hill—at a breathtaking grade of 72%. Built in 1891 to aid escape from floods, the incline provides panoramic views of the city and surrounding mountains.

Unable to enjoy these attractions, we contented ourselves with a stop at the stone-arch bridge, focus of so much death and mayhem. This had been erected by the Pennsylvania Railroad two years before the great flood, and it still looks much the same—with seven majestic 58-foot arches. Colorfully lit with LED lights every evening, it continues to carry countless freights, plus one daily Amtrak in each direction—the Pittsburgh-to-Manhattan Pennsylvanian.

Staple Bend

Southern entrance to the Staple Bend Tunnel along the “Path of the Flood Trail” near Johnstown.

And speaking of trains: I was determined to see the Staple Bend Tunnel on this trip as well.

Lying along the Path of the Flood and originally built in 1833, it’s America’s oldest railroad tunnel. There’s a dedicated parking lot and trailhead for the path to the 900-foot-long tunnel—which gets so dark inside that bikers are requested to dismount.

Inside the Staple Bend Tunnel, where it gets so dark that bikers are requested to dismount and walk.

With the bucolic 2.5-mile trail entirely in shade, highlights included a babbling two-foot-wide brook, where the rivulet’s bed was milk-white from some ongoing mineral deposit; and later—also on our left side—we noted remains of the original rail line, which was built not with wooden ties like today, but rather with two parallel rows of 12”-by-12” stones.

Trail-side brook near Staple Bend Tunnel, with the creek-bed whitened by some sort of mineral deposit.

Again at trail-side near Staple Bend: Numerous stone “sleepers” remain from the Allegheny Portage Railroad, dating back to the early 19th century.

Amtrak’s Pennsylvanian rounds a curve north of Johnstown; the train is just starting its nine-and-a-half-hour run between Pittsburgh and Manhattan.

Preceding even the South Fork Dam, this line was part of the Allegheny Portage Railroad, which hauled boats up and over mountains between two sections of the Pennsylvania Canal network. That landmark system also has its own National Historic Site run by NPS—in nearby Gallitzin.

Happily for this long-time railfan, the Staple Bend Trail parallels Norfolk Southern’s mainline along Little Conemaugh; with careful timing on our final morning, we were able to photograph the eastbound Pennsylvanian just minutes after its 9:05 departure from Johnstown.

Day Tripper

A Norfolk Southern freight, complete with the line’s Lehigh Valley Heritage unit in the second slot, rounds a curve approaching the Allegheny Tunnel in Gallitzin, PA.

Photographed in a torrential downpour, two Norfolk Southern locomotives head toward the Gallitzin Tunnel; having just finished assisting an NS consist over the summit of the Alleghenies, these “helper” engines are returning east for further duty.

If, like us, you stay in Johnstown several days, consider a few worthy side trips:

Bikers and hikers will enjoy the Ghost Town Trail, a rails-to-trails trek along 49 miles of mountain streams and derelict industrial structures. Pennsylvania’s 2020 “Trail of the Year,” it has eight trailheads for those who prefer to bite off shorter sections.

Any and all railfans really must visit the Gallitzin Tunnels and Horseshoe Curve, both less than an hour’s drive.

Overhead shot of Horseshoe Curve from the U.S. Geological Survey. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

A Norfolk Southern freight rounds Horseshoe Curve against gorgeous autumn foliage. (Photo courtesy Missy Gray)

The two popular sites lie along Norfolk Southern’s Pittsburgh line (the one that runs through Johnstown too)—which sees roughly 50 freights a day.

Gallitzin’s double-track tunnel takes trains through the summit of the Alleghenies; a pedestrian overpass crosses the tracks about 100 yards from the tunnel—and it actually has numerous “windows” cut in the protective fencing for clear shots in both directions. This ready access to numerous trains stands in welcome contrast to most rail tunnels, which tend to require a long hard trek followed by a similarly long and boring wait. At the tunnel there’s free parking, a restored Pennsylvania RR caboose (yes, you can go inside) and a free volunteer-run museum.

As for Horseshoe: That engineering marvel, finished in 1854, takes a massive 180-degree loop, making it so much easier for trains to get over the Alleghenies that it put the original portage railroad clean out of business. (And since that portage served the canals—which in turn relied partly on water from Lake Conemaugh—the curve bears a distant causal connection to the flood.)

Also run by NPS, Horseshoe Curve features a small museum, gift shop, restored locomotive on display and of course, a viewing platform; the latter is reached by a long flight of stairs (nearly 200!)—or a funicular railcar. Be aware that the park is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays, and during our trip the funicular was also under restoration. (Check updates on the Curve’s Facebook page.)

Best Town by a Dam Site

The Austin Dam, which burst apart in 1911, unleashing a Johnstown-like deluge toward the town for which it’s named.

The structure still stands beside PA 872 and can be seen first-hand—even along its cracked-open base.

And finally, for folks especially interested in floods—and those who may be open to a longer drive—consider the dam in Austin, PA.

A solid three hours from Johnstown, Austin likewise endured a sudden, massive dam breach; and most of that dam—in this case, a cement one—is still standing. As you look down upon it from PA 872—or walk along its base at the public park there—you can see how the poorly built structure simply opened like a door, unleashing a Johnstown-like onslaught toward the town downstream. But this was 1911, and a hasty phone call from the dam site resulted in a much smaller death toll—78, to be precise.

Returning to Johnstown: the standard source for more information is David McCullough’s excellent 1968 book The Johnstown Flood. Paula and Carl Degen’s The Johnstown Flood of 1889 is also terrific—meticulously researched, beautifully written and loaded with jaw-dropping photos; at a mere 64 pages, it’s practically a must with any visit.

It has been suggested that the popular phrase “Head for the hills!” originated at Johnstown. One hundred and thirty-six years later, it’s not a bad motto for anyone wanting a few quiet, thought-provoking days in the mountains of Southwestern Pennsylvania.

About the Author

Joseph W. Smith III is a writer, teacher and speaker in Central PA. Published in several websites and periodicals, Joe has also penned books on Hitchcock, the Bible, church life and under-the-radar movies—along with a volume of Great Jokes and Riddles. He plays trumpet in a community band; reads 100 books a year; serves as officer in his local church; struggles to keep cheering for the Buffalo Bills; listens to music whenever not sleeping; and maintains a small collection of unused postcards. He can be reached at robbwhitefan@gmail.com.

Joseph W. Smith III is a writer, teacher and speaker in Central PA. Published in several websites and periodicals, Joe has also penned books on Hitchcock, the Bible, church life and under-the-radar movies—along with a volume of Great Jokes and Riddles. He plays trumpet in a community band; reads 100 books a year; serves as officer in his local church; struggles to keep cheering for the Buffalo Bills; listens to music whenever not sleeping; and maintains a small collection of unused postcards. He can be reached at robbwhitefan@gmail.com.All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

Information published on this website and across our networks can change over time. Stories and recommendations reflect the subjective opinions of our writers. You should consult multiple sources to ensure you have the most current, safe, and correct details for your own research and plans.

Frayed Passport is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. We also may share links to other affiliates and sponsors in articles across our website.