The title of Stephen Ambrose’s book on the building of the transcontinental railroad is: Nothing Like It in the World.

That phrase kept revolving in my mind during a recent ride on Amtrak’s California Zephyr, surely the most beautiful train trip in the United States.

Indeed, on our particular journey, the Zephyr’s stunning pilgrimage through the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevadas—with towering crags, plunging rivers, winding rock cuts and dozens of tunnels—easily offset the annoyance of running several hours late the entire way.

It was July 2022; a friend and I took a bedroom for the full Zephyr run from Chicago to California. This would be the fifth of our annual rail vacations together—and the most memorable.

In addition to scenery, we had one engineer who brought his pet mouse along in the cab; we got delayed by a minivan abandoned on the tracks; and we relished an on-board romance between two people from different continents who had never met before. I dare say my friend and I finished this trek feeling like we’d just returned from another planet.

It did not start out auspiciously, however.

All Aboard…Or Not

Union Station in Chicago, starting point for the Amtrak Zephyr—and for many of the railroad’s other legendary long-distance trains.

Having reached Chicago from DC on Amtrak’s overnight Capitol Limited, we found that our 2 p.m. departure had been moved to 3:30—the first of several delays that saw us three hours late out of Denver, four out of Salt Lake City, five out of Elko, NV, and ultimately more than six hours behind at our final destination.

But tardiness is common on Amtrak. Except for the Northeast Corridor between DC and Boston, the company does not own its tracks and is thus subject to the dictates of “host” railroads. This explained some delays, as we sat for an hour behind a crippled freight in Nevada, sometimes ran at reduced speed due to overheated rails and lost priority to other trains after our late arrival in Denver snarled their lineup.

Somewhat less understandable was the initial three-ring circus in Chicago:

Around noon, one PA announcement stipulated a delayed 3:15 boarding; and then suddenly at 1:20, another told us all to line up downstairs, which roughly 100 of us did—only to be sent back up to the main waiting area 15 minutes later. You’ve heard about one hand not knowing what the other is doing, but I can’t help feeling there was a third hand here somewhere. Sheesh.

Room with a View

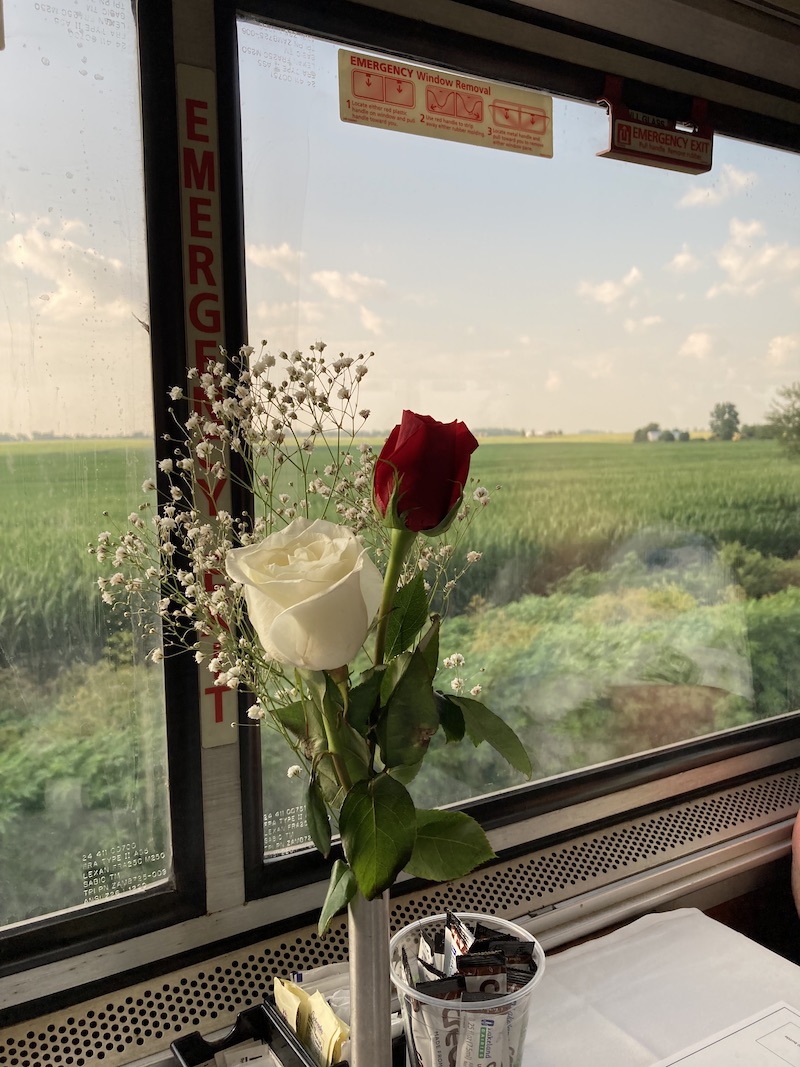

Comfortably ensconced in a spacious “Family Bedroom,” the author gazes out on Illinois farmland as Amtrak’s Zephyr starts its 52-hour journey to California.

We finally left Chicago around 4, settling in under the manful eye of our sleeping-car attendant, Robert. And here I might add that you are allowed to board Amtrak with virtually anything you can carry: six-packs, sandwiches, a pocket-knife, a cooler, a pile of carry-ons; and you need not remove your shoes or your belt. When it comes to long-distance trains, TSA is nowhere to be seen.

On these lengthy runs, John and I prefer the “Family Bedroom” over other available accommodations, which include regular coach seats (very roomy and affordable), along with the snug “roomettes” and the more costly deluxe bedrooms. (These latter all have their own toilet and shower.)

Among its 21 rooms, each bi-level Superliner has one family room that extends the entire width of the car—more than nine feet; this is possible because the hallway through each car is on the upper level, leaving each end of the lower level free for more spacious digs. (On this bottom level, there’s a full-width handicapped room on the opposite end.)

Family rooms feature a generous couch, two additional seats, a pair of fold-out tables and a small closet—plus windows on both sides; this is helpful for scenic runs because you never know which way the car will be facing. At night, the couch flattens into a bed, while a narrower bunk swings down from the ceiling; the room’s five-foot length also allows two smaller kid-beds along one wall—hence its name.

After stopping an hour outside Chicago to fix a broken air-hose, the Zephyr resumed its historic journey, crossing the mighty Mississippi and plunging into America’s heartland.

Fine Food and Friends

The Zephyr’s dining car is ready for dinner just after leaving Chicago on its two-day run to San Francisco; this will be the first of six scheduled meals served to sleeping-car passengers during the trip.

Having debuted in 1949 during the golden age of American trains, the California Zephyr operates daily in both directions between Chicago and San Francisco, taking more than 50 hours to cover its 2,438 miles. And yes, it still crosses much of the route originally laid down for the transcon in the 1860s.

With a departure carefully timed to provide daylight passage over both mountain ranges, the westbound Zephyr spends its first 20 hours crossing the great plains through Iowa and Nebraska.

And here, these Western Amtraks—like the Southwest Chief and the Empire Builder, essentially sisters of the Zephyr—break out their delightful and nostalgic hallmark: the dining car.

Windows run floor to ceiling on the Zephyr’s observation car, which has a cafe-lounge downstairs where riders can buy drinks, snacks and light meals.

Fresh flowers adorn each table in the nostalgic dining car on Amtrak’s California Zephyr.

Three daily meals are included with sleeper tickets, though Amtrak’s current (and hotly contested) policy is that coach riders cannot purchase dining-car meals; they must manage with lighter fare from the separate café-lounge car. Or BYO.

In addition to lunch and breakfast, the diner offers three-course dinners—appetizer, entrée and dessert—along with one complimentary alcoholic beverage. The food is fresh and tasty, and there’s decent choice at all meals. I recommend the morning French toast, the mid-day Monte Cristo sandwich and cheesecake dessert after dinner.

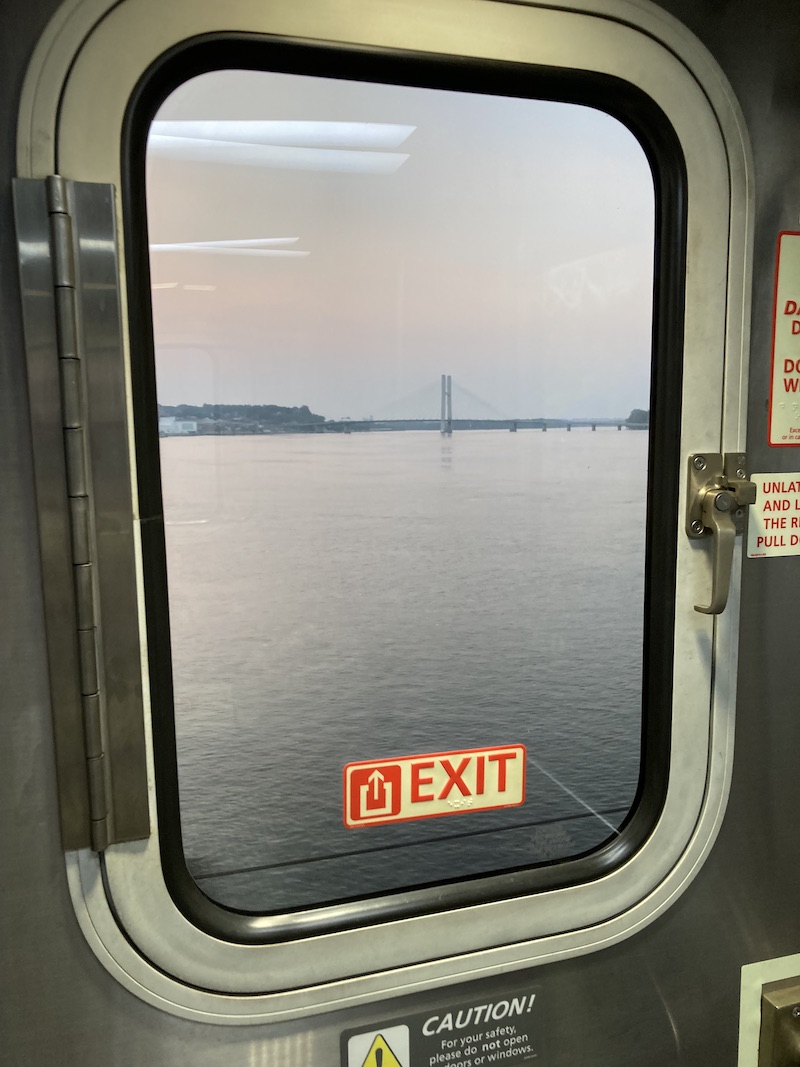

Crossing the mighty Mississippi on the train at Burlington, IA.

That first evening, John and I were seated with Rita, who was on her way to a daughter’s wedding in Colorado—and that’s another great thing about Amtrak: you never know whom you’ll eat with; on any one of these two-day trips, you wind up with a pile of new pals. A long-distance train is a self-enclosed world, and the unharried travelers tend to coalesce into a short-term but very cordial community. It’s the kind of thing that used to occur on transatlantic steamships; but now it happens only on the train.

Into the Wild

Amtrak’s Zephyr has climbed a couple of thousand feet out of Denver as it starts its scenic, eight-hour pilgrimage through the Rocky Mountains; the mile-high city is clearly visible on the plains below. Photo provided by the author’s fellow Amtrak-fan Derek Brown, of Buffie’s Best in Denver.

John is ex-Navy, so next morning we were up around 5 and seated for breakfast by 6 with Jeff and Cole, a father and son traveling to Martinez, CA. The Zephyr, meanwhile, was slated into Denver at 7:15; it arrived close to 10 and didn’t leave till well past 11.

I brought a handheld radio-scanner for listening in on engineers and dispatchers, and it was well-nigh comical hearing them struggle to find a slot for us among the busy freights and commuter trains. In any case, Denver is scheduled as a 50-minute stop, partly for crew change and partly because a lot of new passengers board at that station; from there, this train was sold out to Grand Junction, CO.

We would soon find out why.

Indeed, the jaw-dropping terrain over the next eight hours thrust aside all annoyance about lateness and delays. I’d been on this run twice before, but still stared spellbound as the Zephyr twisted back and forth on its rise into the pine-clad Rockies, with our oncoming track sometimes visible almost directly overhead.

Observation car and two following coaches bring up the rear of Amtrak’s Zephyr as it winds along the Colorado River through the Rocky Mountains.

Majestic Gore Canyon from Amtrak’s Zephyr as the train makes its way through the Rockies.

I lost count of tunnels at around 32, though I did note the famous and majestic Moffat Tunnel, which passes under the continental divide. Named for railroad pioneer David Moffat, who designed much of this difficult route 120 years ago, it is exactly 6.2 miles long—though at 7.8, the Cascade Tunnel on the Empire Builder is America’s longest. In addition to roughly 15 trains a day, the Moffat also carries pipes that provide drinking water for Denver.

Upcoming tunnel awaits Amtrak’s Zephyr as it skirts the Colorado River through scenic Byers Canyon.

Big sky and river from Amtrak’s Zephyr as it traverses the Rocky Mountains. If you want to build a railroad through tough terrain, follow a river—in this case, the Colorado, which this twisty trip traces for 400 miles.

Seen from Amtrak’s California Zephyr, the mighty Colorado stretches out along a sandbar in the heart of the Rocky Mountains.

Both the Colorado River and Amtrak’s Chicago-to-Frisco rail line run through craggy Byers Canyon in the Rockies.

A pair of Amtrak workhorses, the now-aging GE Genesis units, appear briefly in the train window as they lead Amtrak’s Zephyr toward a tunnel along Byers Canyon.

By now the Zephyr had climbed 4,000 feet out of the mile-high city and was about to enter its most scenic segment, slithering along the sheer rock walls of Gore and Byers canyons, while the roiling Colorado rushes past more than 100 feet below. At times you look ahead where two or three tunnels in a row cling to the cliffside; at others, you glance down to see rafters honoring a time-tested tradition by cheerfully mooning the train.

I have long contended that inside the soul of every middle-aged man is an adolescent boy who never grew up, and frankly I was dying to reciprocate this gesture of good will; but at age 62, that would give a whole new meaning to “indecent exposure”—plus I didn’t want Robert to have to clean the windows.

Eagle-Eyed Diners

Family bedrooms have one minor drawback: The windows are comparatively small. While I was standing in the upstairs corridor for better views of Gore, I met Shania, a chipper young Australian who, I had noted, seemed inseparable from a similarly cheerful young American named Gavin. I’d assumed they were a couple, but in fact they had only just met at Chicago’s Union Station, and now…well, maybe that had become a couple. When I grabbed a photo of them looking lovey-dovey on the final California platform, I felt certain they were headed somewhere together.

That evening John and I dined again with Jeff and Cole, the latter of whom was a good deal more talkative than he had been at 6 a.m. I pointed out one adult and two juvenile bald eagles in a tree on the riverbank, bringing my eagle-spotting total to eight since Denver.

Other sightings included deer, hawks, turkeys, herons, ducks, geese, osprey, egrets, cormorants and a lovely kestrel; but actual wildlife seemed sparse on this trip. On earlier Amtrak journeys, I had seen a beaver in a track-side creek—and most memorably, a grizzly bear from the Empire Builder as it passed through Glacier National Park.

By now we were almost through the mountains and paralleling Interstate 70, whose graceful curves and columns have been cunningly engineered to cut through these canyons without cluttering up the scenery. It is often double-decked and features many tunnels—including the Eisenhower, which is both the longest and highest in the interstate system: 11,158 feet of elevation as it passes under the continental divide.

Breakfast in the Desert

Sun peaks over the Nevada horizon, as seen from a family bedroom on Amtrak’s California Zephyr. The train normally traverses these barrens in the middle of the night, but a four-hour delay allowed its passengers this 5 a.m. glimpse of sunrise and desert.

There’s something otherworldly about the middle day of a two-night rail journey. With no responsibilities except to dine and gaze out the window, and with precious little internet or cell service, one feels almost totally unplugged—an increasingly rare experience in modern-day America. There’s a spacious, almost intoxicating freedom of a sort I have felt almost nowhere else in life.

Again on the second morning we arose at 5, with a blood-orange sun blazing through our window as it peeked across the desert horizon. At breakfast we were joined by Gale and Alex, who hailed from Martinique. This French-speaking couple managed modest English, with a heavy accent and a limited vocabulary that expanded a bit during our meal; meanwhile I dug up my pathetic French, which consists of maybe five words. (Fortunately, at parting, I did remember bonne chance.)

The Zephyr normally crosses this Nevada wasteland at night, so we were looking out on a barren, baking landscape rarely seen by train. When Alex gestured toward it and managed to ask, “What do they do with it?”, I had no answer.

Nothing Like It

Donner Lake in the Sierra Nevadas as seen from Amtrak’s California Zephyr. Nearly 6000 feet above sea level, this vast body of water was named for the infamous pioneer party that got stranded in a snowstorm and resorted to cannibalism for survival.

Amtrak swaps out its pair of engineers every four hours, which allows passengers to debark briefly for a “fresh-air stop,” colloquially known as a smoke-break. (Good luck reconciling those two labels.) After breakfast, John and I stepped into an oven-like day in Winnemucca, NV. As I thanked the departing engineers, I saw that one was carrying, along with his gear and knapsack, a small, clear plastic box; inside it, a white-and-brown mouse rested comfortably on a bed of wood chips. I was so taken aback I couldn’t say a word. Only later did I wonder whether he had an unusually aggressive cat at home. Or maybe this pet is his engine-driver’s good-luck charm.

We lunched with another father and son—a pair of Mormons who’d boarded in Salt Lake City—and then the Zephyr started climbing toward its second scenic segment: the Sierra Nevadas, including the Truckee River, plus Donner Lake and Donner Pass. These latter locales are named for the ill-fated pioneer party that got stranded in one of the range’s legendary snowstorms and resorted to cannibalism for survival.

Tunnels in the Sierra Nevada range as seen from the very back window on Amtrak’s California Zephyr.

Tunnels in the Sierra Nevada range as seen from the very back window on Amtrak’s California Zephyr.

With nonstop twists and turns, sprawling mountain vistas and another dizzying array of tunnels, the Zephyr’s route had been even harder to lay out than the one through the Rockies—largely because of snow. In fact, many of the line’s lengthy “tunnels” are actually sheds that keep snow off the tracks. As Ambrose recounts, the crews originally laying rails for this route in the 1860s were sometimes working under 40 feet of snow, with huge vertical shafts driven to the surface for ventilation.

Nothing like it, indeed.

Forbidding mountain terrain in the Sierras necessitated many twists and turns when laying out this line in the 1860s. This particular curve is viewed from the back window of Amtrak’s Zephyr as it makes its way toward San Francisco.

The Western long-distance trains usually include an observation car with floor-to-ceiling windows; these have several tables and an array of outward-facing chairs—but I like to leave it open for coach passengers, who often need to stretch out a bit.

So after two hours shuttling from side to side for the best views in our sleeper, I headed to the very back of the consist, where a single small window looks out on passing track and terrain. This proved a terrific vantage-point for more tunnels, bridges, curves and chasms; I must have shot 100 pictures, including some of Interstate 80, the main highway near my home in Pennsylvania. As I snapped a snowshed under this cross-country route, I could almost hear myself say, “Fancy meeting you here.”

The author captured this dashing view from the back window of Amtrak’s California Zephyr. It is not a tunnel per se, but rather one of many man-made sheds on the line, built to protect the tracks from the Sierra Nevadas’ legendary snowstorms.

The Last Supper

It now became clear that we’d be six hours late for our scheduled 4:10 p.m. arrival in San Francisco. So the dining-car crew announced they would serve an extra dinnertime meal to all passengers—even those in coach. Being somewhat last-minute, this was nothing special (beef stew, along with a vegetarian option); but it did allow us to make our last two new friends: Angie, a pastor returning from a conference, and the older Joan, whose two grandsons were taking her on an Amtrak dream vacation: four or five trains around the country, with various stops including baseball games in Denver and at Wrigley Field, along with a concert by James Taylor. Now that’s family love.

Speaking of this courtesy meal: Here’s a well-deserved shout-out to our hard-working diner staff—Chris, Dez and Justin; let’s face it, they had basically been on their feet from 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. for two whole days. Not to mention the anonymous chef laboring in his lower-level kitchen. I spotted him once in the diner between meals, noshing on a plate of strawberries; next time I passed, he was leaning back in his table-seat, fast asleep.

Car on the Tracks!

Evening descended as we rushed toward our terminus, stopping at several California towns, including Martinez. Here, our assistant conductor miraculously rescued a cell-phone left aboard by Jeff or Cole, getting it out to them on the platform before our departure. What a pro!

Missing the usual daylight run along the bays of Suisun, San Pablo and San Francisco, we were nonetheless happy to be reaching the last station at a still-reasonable hour for cabs and Ubers. The Zephyr, incidentally, finishes not in San Francisco but across the bay in Emeryville; passengers are then bussed over to the city—but John and I had already determined to skip the Amtrak bus and get an Uber directly to our hotel.

And then we ground to another shuddering halt only two miles from our destination. The conductor informed us that an automobile was sitting on the tracks ahead—but it turned out the car was actually on an adjacent track, not ours. As we pulled slowly past, I could see a minivan situated not across the track but rather along it, with driver-side tires between the rails—as though the owner had tried to turn his vehicle into a train. Oh, well; at least he left his flashers on.

Two Tickets to Paradise

Six hours late at the end of a 2400-mile journey, Amtrak’s California Zephyr has finally arrived at the Emeryville station in California—right across the bay from San Francisco. The engineer leans out looking back, perhaps to make sure his train-set made this arduous trip in one piece.

Before long, everyone piled gratefully off at Emeryville, with many fond photos and farewells. It’s a good idea to tip your sleeping-car attendant, the more so with us, as we learned that Robert, who had just finished up a 60-hour shift, would shortly do the entire trip again, starting all over at 9 next morning on the returning Zephyr. Like the dining-car staff, these guys generally work four shifts a month: both ways on two trains, logging at least 150 hours. John and I would’ve happily returned with them on the eastbound, but we both had duties and planned to fly home in the morning.

Shania and Gavin have just stepped off the Zephyr at its California terminus in Emeryville, California. She from Australia and he from the United States, the pair had met just two days before, when preparing to board at Chicago’s Union Station. It seems they got to know each other pretty well during our 58-hour run.

Speaking of which: If a six-hour delay sounds irritating, consider the madhouse of SFO airport on a summer Saturday. In my case, this included the longest security line I have ever seen, filling the entire rope queue and stretching another 100 yards down the concourse; worse yet—for the first time in my life—American Airlines canceled my flight and then rebooked me 70 minutes earlier at a different airport.

Even without that ugly contrast, the California Zephyr was two days in paradise.

About the Author

Joseph W. Smith III is a writer, teacher and speaker in Central PA. Published in several websites and periodicals, Joe has also penned books on Hitchcock, the Bible, church life and under-the-radar movies—along with a volume of Great Jokes and Riddles. He plays trumpet in a community band; reads 100 books a year; serves as officer in his local church; struggles to keep cheering for the Buffalo Bills; listens to music whenever not sleeping; and maintains a small collection of unused postcards.

He can be reached at robbwhitefan@gmail.com.

Joseph W. Smith III is a writer, teacher and speaker in Central PA. Published in several websites and periodicals, Joe has also penned books on Hitchcock, the Bible, church life and under-the-radar movies—along with a volume of Great Jokes and Riddles. He plays trumpet in a community band; reads 100 books a year; serves as officer in his local church; struggles to keep cheering for the Buffalo Bills; listens to music whenever not sleeping; and maintains a small collection of unused postcards.

He can be reached at robbwhitefan@gmail.com.

All images with the exception of image #7 courtesy of Joseph W. Smith III—image #7 provided by Derek Brown, of Buffie’s Best.

Frayed Passport is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. We also may share links to other affiliates and sponsors in articles across our website. If you have questions or concerns, please contact us.