Dive into the Past! Let’s Go Hunting for Megalodon Teeth in Florida’s Gulf Coast

By: Frank Morrow

Skip to Section

During the Miocene Era, the ocean rose, covering the land—and the megalodon and the whales they hunted swam in the warm seas. Then in the Pleistocene Era, the ocean fell, and the land left behind became home to the mammoth and other animals.

In shallow waters off the Gulf Coast of Florida are fossil beds containing evidence of these animals.

Scuba diving for megalodon teeth has always sounded like a fun adventure. So I contacted Captain Mike of Aquanutz Fossil Dive Charters in Venice, Florida to book a seat on the boat in March 2022. To dive on this trip, you must be at least an Open Water scuba diver with 15 logged dives or better, and you need to be very comfortable in the water on your own.

A megalodon tooth up close

He warned me that the visibility could be 20 feet or less. It is very hard to keep track of a buddy as you concentrate on looking for fossils, even with the depth of the water being only 20 feet. He also noted that the water in March is about 70 degrees Fahrenheit, so a 7mm wetsuit and hood are needed. As you look for fossils, you are not kicking around and generating any heat, so it’s easy to get chilled.

This charter is for three dives; you can expect to be on the boat for about eight hours. Each diver gets three 80-cubic-foot air cylinders—with six divers and two crew, that means 24 cylinders total. The Dive Charter provides each diver with lead weights and a fossil collection bag.

Once I stated that I am an instructor and dive in Pennsylvania’s cold and muddy waters, Captain Mike’s concerns were alleviated.

One of the dive sites

At 7:30am, we met the Aqaunutz and her crew at the Marine Park. We handed our regulators and BCDs to the Divemaster so she could set up each kit. We were in our wetsuits or drysuits, and Captain Mike inspected us to ensure we would be warm enough. I boarded the boat with my mask, snorkel, fins, camera, water, and snacks. It was a relatively short ride to the fossil beds.

Captain Mike set the anchor and described the area in which we would be looking.

The first person in the water was the Divemaster, who ensured the conditions were safe. With her ok, we took turns rolling backward over the side (yes, divers roll backward over the side of a boat to enter the water—if we rolled forward, we would fall onto the boat’s deck).

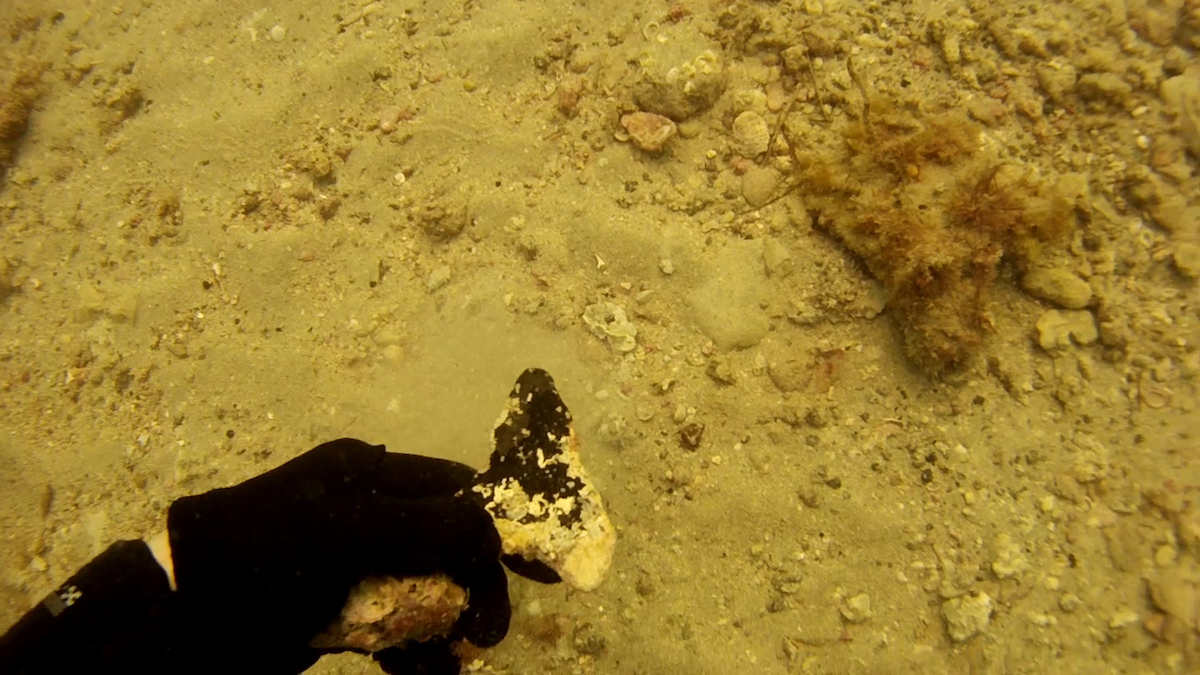

As I began my search along the bottom of the Gulf, I kept the samples of megalodon teeth that Captain Mike showed us in mind. Black and heavy, the fossils are now rocks. Coral, bone, and shell are lighter than the fossils, so I picked up anything that looked interesting and felt its weight. Of course, I wanted to find at least one megalodon tooth, but I was also looking for other shark teeth and bone fragments of the whales, dugongs, and mammoths. I looked for straight lines, regular shapes like the triangle of a shark tooth, or the curve of a rib. I realized that the fossils would have some aquatic growth on them. Anything that might be a fossil was placed in the bag. After an hour, I returned to the boat with a full bag containing two megalodon teeth and many rib bones from whales and dugongs.

A discovery

The boat had a very strong ladder situated between the two outboard motors; the ladder was let down once the anchor was set. When I reached the ladder at the end of the first dive, I handed up my fins and climbed out. My bag of fossils was dumped out, and the crew identified each. Some were fossils, and some were rocks. Each diver’s finds were placed in a separate bin for safekeeping.

The captain pulled the anchor up when the last diver boarded and went to another fossil bed. We exchanged our used cylinders for fresh ones. Then the diver who was last returning was the first diver back in for another dive. On the second dive, I found more rib bones, a lemon shark tooth, an ancient stingray spine, and a whale ear bone.

A tooth

We repeated the process for the third dive. This time I found more ribs, but I left them there. I wanted to find more megalodon teeth or something unique. As I scoured the bottom, I found broken teeth—then, toward the end of the dive, I saw a small, rough-looking cylinder. I picked it up, and it was heavy. It appeared to have a hole running down the middle. Dare I hope? After looking for another 15 minutes, I made my way back to the boat. As I climbed the ladder, the Divemaster saw that I did find a piece of a tusk, either mammoth or mastodon.

After all the divers were back on board and the equipment secured, we headed back to the dock. At the dock, we disembarked and gathered our gear and treasures, and we admired each other’s finds. Each of us had about two dozen fossils to take home.

A successful day of fossil diving.

The tusk

Tips for success when diving for fossils and the impressive Megalodon teeth:

- Book early with one of the many reputable boat charters you can find in the area.

- Be an experienced diver with recent dives under your belt.

- Know your limits; when you are tired or cold, it is time to end the dive.

- Expect very low visibility and lots of contact with the bottom of the Gulf. The fossil beds are not delicate coral reefs, and there is a current to manage.

- If you don’t want to dive in cold water, go in the summer.

- Listen to the briefing; follow the crew’s instructions carefully, as they have done this hundreds of times.

About the Author

Facebook: A Water Odyssey Scuba

Inline images courtesy of the author. Featured image by Carla Burke from Pixabay.

Information published on this website and across our networks can change over time. Stories and recommendations reflect the subjective opinions of our writers. You should consult multiple sources to ensure you have the most current, safe, and correct details for your own research and plans.

Frayed Passport is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. We also may share links to other affiliates and sponsors in articles across our website.