Sandy Island: The South Pacific Island That Was Discovered by Whalers—Then Undiscovered by Ham Radio Operators

By: Sarah Stone

Skip to Section

Sandy Island was real—at least, according to explorers, atlases, and even Google Earth.

The island, reported to be 1.5x longer than Manhattan, had been displayed on maps of the Coral Sea since 1876. Yet in 2000, when of all people, a group of ham radio enthusiasts tried to find it, it just…wasn’t there. And then, 12 years later, a team of scientists sailed to its supposed location and found the same thing the radio operators did: nothing.

How did an island that never existed end up on world maps for over a century? And how did it take until 2012 to finally correct the mistake? The bizarre story of Sandy Island is one of cartography errors, assumptions, and the lingering power of a simple mistake.

The “Discovery” of Sandy Island

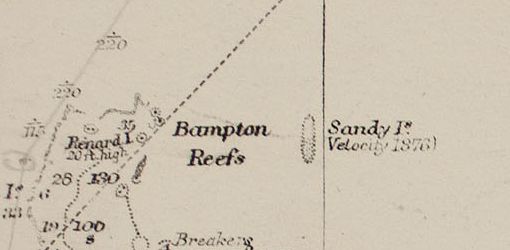

Image via R.C. Carrington, of the Hydrographic Office, accessed at Wikimedia Commons.

The earliest known mention of what might be Sandy Island dates back to September 1774, when Captain James Cook noted a point called “Sandy I” while traveling through the area. It was also potentially spotted by French navigator Antoine Brune d’Entrecasteaux in 1792, indicated as “Ile de Sable.” Just about a hundred years later, in 1876, the Australian whaling ship Velocity crew reported the supposed island’s existence as characterized by heavy breakers and sandy islets—but it’s not totally clear if:

- They were referring to the same thing Captain Cook saw, as the 1876 notation was hundreds of kilometers west of “Sandy I”

- They were referring to an island at all or just noting hazardous conditions in the area—a common practice with navigation notation

Without satellite imagery or modern navigation tools, 18th- and 19th-century sailors relied on visual confirmation and rough mapping techniques—for a fascinating example of how creative, intelligent, and accurate these techniques could be, read this article about Cook’s surveying strategies. If explorers saw something that looked like an island—especially from a distance—it was sometimes assumed to be newly discovered land. Once an island appeared on a map, it was typically copied onto future maps and atlases without much verification.

Cartographers began adding Sandy Island to maritime charts within a couple of years of Velocity‘s recording, and with no one immediately challenging its existence, the island became an accepted part of geographic knowledge. It was featured in an 1879 Australian maritime map, the 1895 British Admiralty chart, a New Zealand chart of the Pacific published in 1908, National Geographic Society maps, and many others all the way up to 2012, when it was still listed even on Google Earth.

A Century of Belief in a Fake Island

Sandy Island remained a mystery for decades—not because people doubted its existence, but because no one seemed to visit it. It was common in the 1800s to note islets, exposed reefs, and other navigation hazards (like those in the more treacherous areas of the Coral Sea) on nautical charts without returning to fully map the precise location and object—so spots like our mysterious Sandy Island stayed on maps until their existence could be positively disproven. Ships charting the Coral Sea over the years failed to find it, but the assumption was that they must have been looking in the wrong place.

By the time the 20th century rolled around, Sandy Island was firmly established on maps all over the world—but with evolving technologies and more opportunity to travel to less-charted locations, cartographers became increasingly skeptical about the island’s existence. Some even placed the internationally recognized abbreviation “ED”—”Existence Doubtful“—next to Sandy Island.

In 1974, Sandy Island was removed from the French Hydrographic Service’s official charts thanks to their flyover mapping campaign and a seafloor mapping conducted by their counterparts in Australia, which found no evidence of a reef shallow enough to even be confused for an island in that area. Yet, it remained in many other maps for nearly 40 years, including the World Vector Shoreline Database developed by what’s now the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

“TXØDX Challenges National Geographic”

Let’s talk about DXpeditions.

These are journeys to exotic, remote, or restricted locales by amateur radio operators and listeners. They began in the late 1920s as a way to explore and establish communication across faraway areas—”DX” here is shorthand for “distance” or “distant.”

Some locations—like tiny islands, unclaimed territories, or politically restricted regions—have few or no active ham radio operators. This makes them rare on the air, so DXpedition teams travel to these remote spots, set up antennas and transmitters, and spend days or even weeks making as many radio contacts as possible. Even if you don’t have the chance to travel with a team in person, you can participate as a listener by making radio contact once the team has established communication—you can see in the video above that these small expedition groups can make hundreds of thousands of contacts around the world at these tiny, far-flung operating sites.

There are sponsors and awards for these expeditions, both by large and small clubs. Probably the most recognized award is the DX Century Club (DXCC), sponsored by the American Radio Relay League (ARRL). This award is given to those who successfully contact and confirm 100 different geographic entities defined by the organization.

Now, in 2000, the Association des Radio Amateurs de Nouvelle Caledonie (ARANC) determined to establish communication in the extremely remote Chesterfield Islands as part of their DXCC bid. The Chesterfields are an archipelago of 11 tiny, uninhabited coral islets (all put together, less than 10 square kilometers of land area) about 550 kilometers northwest of New Caledonia. For two years leading up to their voyage, the team, comprised of international members, worked diligently to get the island group added to the DXCC database of eligible locations. They gathered a crew, cleared travel, set the call sign TXØDX for their expedition, and by March 2000, almost all of the hurdles had been cleared except for one: the comparatively massive Sandy Island—printed on a number of modern maps, including those on the National Geographic website. Confusingly, it was missing from other maps, such as the recently updated Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World.

But if the expedition team was focused on the Chesterfield Islands, why should they care about Sandy Island?

Well, it’s because of the DXCC eligibility rules for new entities. According to a TXØDX bulletin dated April 10, 2000, “It is required that there should be an open water separation of at least 350 kilometers between the westernmost point of FK-land and the easternmost point of Chesterfield Islands. If Sandy Island existed, the separation would not be sufficient, and the bid to make this a new DXCC entity would have failed.”

They forged ahead anyway, departing from Koumac, New Caledonia on March 19—but before arriving at the Chesterfield Islands, they took a little jog out of the way:

“On the way to the Chesterfields, the TXØDX group made a slight detour to the area where intervening reefs are indicated on some older maps. The team was able to confirm the French Navy’s documentation that the claimed islands simply do not exist. Thus, the 350-kilometer open water separation between New Caledonia and the Chesterfields is assured, and the concerns expressed by some in the DX community can be put to rest.” (TXØDX Bulletin 15)

The team arrived at the Chesterfields on March 23 and anchored their ship about 90 meters from one of the southern islets. Shallow coral made it challenging to get any closer, so the team hustled to transport their equipment to land during high tide when it was a bit more manageable (despite the 100-plus-degree heat and occasional rain). That same day, the ARANC was admitted to the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU), meaning that as soon as they went live from the Chesterfields, QSOs—contact made and confirmed between two amateur radio stations—to the island group could count toward this expected new entry in the DXCC entity database.

They hit the airwaves at midnight on the 23rd and accumulated over 72,000 QSOs over the next six days.

After returning to New Caledonia on March 31, the TXØDX team posted the aforementioned bulletin dated April 10, calling out National Geographic Maps for their inaccuracy in displaying the nonexistent Sandy Island, and noting that even looking at NOAA satellite imagery, there’s clearly deep blue sea where the island was said to exist. The response? “Our maps are hopelessly outdated for this area.”

While it would take another 12 years for a scientific research expedition to confirm what the ham radio operators already knew, the careful planning, deliberate efforts, and successful transmission from the Chesterfield Islands ensured this little archipelago was added to the DXCC entity database.

2012: Sailing to an Island That Wasn’t There

The “undiscovery” of Sandy Island wasn’t made official until 2012. In late November of that year, University of Sydney geologists aboard the research vessel Southern Surveyor embarked on a 25-day sea floor mapping exercise. As they approached the coordinates of Sandy Island, they expected to see land emerging on the horizon. But instead of an island bigger than Manhattan, they found nothing but open ocean.

The team checked satellite images, GPS coordinates, and historical records to confirm they were in the right place. Everything indicated they were precisely where Sandy Island was supposed to be—except there was no land in sight.

Curious about the discrepancy, and aware of the island’s dubious map placements, the researchers used depth-sounding equipment to measure the seafloor. If the island had been real, there should have been shallow waters or land formations beneath them. Instead, their instruments showed that the ocean in that area was more than 1,400 meters deep—far too deep for an island to have ever existed there.

At that moment, the truth became undeniable: Sandy Island had never been real.

How Did Sandy Island Stay on Maps for So Long?

If Sandy Island never existed, how did it end up on official maps and atlases for over a century? There are a few theories that might explain this long-lasting mistake, but the most straightforward is that it was a simple cartography error that kept spreading.

Maps in the 19th century were often hand-copied from previous maps, which meant errors could easily be repeated and passed down for generations. If a single early mapmaker mislabeled a location or copied incorrect data, that mistake could have been reproduced in atlases, naval charts, and even modern digital maps—exactly what happened.

According to a report in Eos:

“Some datasets derived from satellite imagery, such as sea surface temperatures, also indicated the presence of an island—for example, sea surface temperatures were absent over the island, suggesting the presence of land. However, it became apparent that a landmask was applied to these data sets during preprocessing as a way of differentiating between land and water; the land mask allows researchers to more easily use different algorithms to analyze water or land. As WVS [World Vector Shoreline Database] has become the standard global coastline data set used by the scientific community, errors that existed in WVS propagated into data sets that use a landmask. Therefore, rather than providing independent evidence for the existence of an island, the appearance of Sandy Island in bathymetry and satellite imagery data sets sprang from spurious digitized geometries in the WVS database.” (Eos, Vol. 94, No. 15, 9 April 2013)

After the 2012 expedition, Sandy Island was officially removed from maps, atlases, and scientific databases. Google Maps deleted it from its system, and major publications like National Geographic corrected their records.

While modern maps are far more accurate, mistakes still happen. Even today, occasional errors in GPS data, satellite images, and digital maps lead to misplaced locations, nonexistent roads, and mislabeled areas. It took 136 years for the mistake to be recognized and erased, making Sandy Island one of the most famous phantom islands in history.

Before you go! you might love this article: What Are Phantom Settlements? Paper Towns & Mountweazels in Maps Around the World

About the Author

As the editor-in-chief of Frayed Passport, my goal is to help you build a lifestyle that lets you travel the world whenever you want and however long you want, and not worry about where your next paycheck will come from. I've been to 20+ countries and five continents, lived for years as a full-time digital nomad, and have worked completely remotely since 2015. If you would like to share your story with our community, or partner with Frayed Passport, get in touch with me using the form on our About page.

As the editor-in-chief of Frayed Passport, my goal is to help you build a lifestyle that lets you travel the world whenever you want and however long you want, and not worry about where your next paycheck will come from. I've been to 20+ countries and five continents, lived for years as a full-time digital nomad, and have worked completely remotely since 2015. If you would like to share your story with our community, or partner with Frayed Passport, get in touch with me using the form on our About page.Featured image by Jeremy Ricketts on Unsplash

Information published on this website and across our networks can change over time. Stories and recommendations reflect the subjective opinions of our writers. You should consult multiple sources to ensure you have the most current, safe, and correct details for your own research and plans.

Frayed Passport is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. We also may share links to other affiliates and sponsors in articles across our website.