Peru’s Attic: A Walk through Lima’s Museum of Archaeology

By: Mike Gasparovic

Skip to Section

Museums in Peru have a romance not shared by their U.S. counterparts. Where the latter are all sleek LCDs and interactive displays, the former are more like curiosity shops: jumbled collections of artifacts where at any moment, you’re liable to stumble across an odd treasure that opens a window onto a vanished world.

A case in point is the Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology, and History located in Lima’s quiet district of Pueblo Libre, about 20 minutes by taxi from Miraflores.

Here you won’t find computer-animated displays or IMAX movie theaters, and the exhibit descriptions occasionally suffer from confusing chronology or faulty (or missing) English translations. Notwithstanding, this museum is an absolute must-see, not only for the thousands of fascinating items it houses, but for the historical overview it provides of one of the wellsprings of Latin American civilization.

Stellae and Skulls

The archaeological museum is organized chronologically. No sooner do you enter than you’re thrust into the mists of Peru’s remote, pre-Inca past.

Several early exhibits are particularly arresting. Among them: a model of Chavín de Huantar, a major ceremonial precinct constructed c. 800 B.C. by the peaceful Chavín people over a maze of underground galleries and excavated by the great archaeologist Julio Tello in the 1920s. Situated at the conjunction of the Andean sierra and the Amazon rainforest, the grounds are today a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The museum has several Chavín treasures on display, including the Obelisco Tello, an engraved monolith that probably served as a sundial in the temple’s main court, and the Raimondi Stela, a seven-foot granite slab found in a peasant’s hut by the historian Antonio Raimondi in 1874. The stela’s intricate design can be read two ways: right side up, it depicts a jaguar-faced god with a fanged headdress; upside down, it shows three serpent snouts supporting a leering deity.

Equally intriguing is the hall dedicated to the Paracas culture, located along Peru’s southern coast near Ica. In the 1910s, the indefatigable Dr. Tello noticed in Lima’s markets an influx of ancient textiles whose origin he couldn’t identify. He traced them to the arid lands south of Lima, where he eventually discovered a vast necropolis, or city of the dead, unknown to previous archaeologists.

Today the Paracas peoples are celebrated for their burial techniques, which involved trepanning the skulls of their dead and interring them with their belongings in bottle-shaped tombs. The museum’s hall dedicated to their culture was recently remodeled, and features informative videos and a grisly row of hollowed-out crania, along with a spectacular life-size reconstruction of a caverna, or burial plot.

Sexy Pots

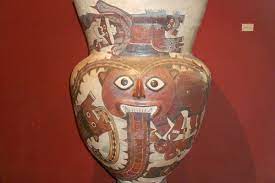

Nazca Vase at Lima, Peru’s Archaeology Museum.

The museum’s second arcade is dedicated to the later regional cultures that sprang up in the wake of the Chavín. These include the Nazca, Lima, Moche, and Wari, in a sequence culminating with the Incas in the 1400s.

The Moche in particular were outstanding artisans; their pottery and metalwork show an imagination scandalous in its realism, as well as a ribald sense of humor. Many of their statues appear to be caricatures of real people. Check out the ceramic vessels depicting various types of sexual activity (R-rated artifacts abound here), as well as the underground room full of gold masks and jewelry.

Conquered and Conqueror

Of course, no museum of Peruvian history would be complete without the Incas, who figure abundantly in the museum’s Tahuantinsuyo Room. Kids will appreciate the replicas of Machu Picchu and of the main square at Cuzco, while adults will have fun examining the textile samples and quipus, knots used by Inca bureaucrats for record-keeping.

The exhibits take a somber turn in the hall dedicated to the Conquest. Here, amidst portraits of the men responsible for subjugating Peru’s native populations, you’ll find reminders of the violence that has plagued the country for the past 500 years. One display juxtaposes Spanish weapons with the crosses and flagella used to impose European religion on the indigenous peoples, while another features artwork cataloguing the caste system set up by the race-obsessed Spaniards, traces of which still linger in Peru today.

Progress

Presidential Carriage, Republican Era, at Lima, Peru’s Archaeology Museum

Oppression isn’t given the last word, however. The final galleries are dedicated to Peru’s advances over the past two centuries, starting with the revolutions at the start of the 19th century and culminating with the 1960s’ agrarian reforms. Don’t miss the first copy of El Peruano, Peru’s newspaper of record, or the portrait hall dedicated to the country’s presidents.

Nor should you overlook the building itself. Unofficially named Quinta de los Libertadores, it was formerly the residence of the Peruvian Viceroy and then, briefly, of the two great heroes of Latin American independence, José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar.

In honor of the latter, a central wing of the museum has been fitted out with artifacts from their campaigns, including the sabers they used in battle and facsimiles of the Capitulation of Ayacucho, which ended Spain’s empire in South America.

Visit

Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Anthropología y Historia

Plaza Bolívar (Pueblo Libre)

463-5070

About the Author

Mike Gasparovic is a freelance writer, editor, and translator. He devotes his free time to studying the history, art, and literature of the Spanish-speaking world and learning about its people. He currently lives in Lima.He currently lives in Lima and wrote this article on behalf of South American Vacations, a leading provider of tours to Peru, including destinations such as Lima and much more.

Inline images courtesy of the author. Featured image via Unsplash.

Information published on this website and across our networks can change over time. Stories and recommendations reflect the subjective opinions of our writers. You should consult multiple sources to ensure you have the most current, safe, and correct details for your own research and plans.

Frayed Passport is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. We also may share links to other affiliates and sponsors in articles across our website.